ART CONSERVATOR

DIGITAL

A PUBLICATION OF THE WILLIAMSTOWN + ATLANTA ART CONSERVATION CENTER

VOLUME 15. NO.2 What

Lies

Below

What Lies below: eighteenth century fabric supports present in the portraits of

Jacobus and Jan Baptist Van Rensselaer

MONTSERRAT LE MENSE | SENIOR PAINTINGS CONSERVATOR

The Williamstown Art Conservation Center (WACC) has been privileged to be working with the Albany Institute of History and Art (AIHA) on the care of several eighteenth-century Dutch patroon portraits in their collection (c. 1700-1735). In considering a painting’s conservation, it is helpful to understand both the materials and techniques an artist used to inform our treatment decisions, long-term preservation strategies, and contemporary interpretation of the work itself --how they were made and how they have aged. The treatment of thirty-five Dutch patroon portraits belong to AIHA allowed the department of paintings conservation at the WACC to make observations about the fabric supports used by various Dutch Patroon or Limner artists during the early to mid-eighteenth century in the colony of New York.

We were fortunate to treat two pendant portraits of brothers from the powerful Rensselaer family: Jacobus van Rensselaer (1713-62) and Jan Baptist van Rensselaer (1717-1763), painted by John Watson (1685-1768) in 1735 (figs. 1-2). John Watson was a Scottish-born emigrant artist, and similar to his Dutch Limner contemporaries, he started out as a craftsman, painting houses and signs. At some point, either prior to emigration or during his time in the colonies, he went under rigorous artistic training which is evidenced in the manner he was able to paint the likenesses of the sitters and their clothing: the portraits are not considered “primitive” in comparison to his contemporaries. He went on to paint several portraits of the Van Rensselaer family, becoming known as the “Van Rensselaer Limner” [1]. While the portraits of these brothers likely stayed together as they aged, they display a contrast in the history of their preservation.

Of the two paintings -- roughly the same date, both oil on artist-prepared canvas-- one remains largely intact with all original materials, while the other has had several interventions from previous conservation campaigns due to structural instability. In a gallery or museum setting, it might not be possible to tell that Jan Baptist (fig. 2) has been lined to a secondary support fabric and Jacobus (fig. 1) has not. It is a rarity that the canvas for the Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer has never been lined over its three-hundred-year-old history; its relatively untouched canvas offers a window into the supports available in this understudied period. This presented a good opportunity to examine them closely from the sides, backs, and edges to yield comparative information on how they were constructed, how they aged, and how they were repaired. and how these observations impacted the treatment decisions to preserve these significant examples of the earliest artworks made in America.

The Rensselaerwyck Manor

The quality of materials used by artists for these portraits are dependent on various aspects: notably, the availability of materials in the American colonies due to British trade regulations, the amount of money that the client could pay the artist for a portrait, and the artist’s training or skill set. The most famous and wealthiest Dutch Patroonship in the northern Hudson Valley at the time these portraits were made, was Rensselaerwyck--- home to the powerful van Rensselaer family that owned land stretching across multiple counties surrounding the present-day New York Capital District, Albany. In fact, it was the most successful Dutch Patroonship that continued to prosper after the British takeover from the Dutch government in 1664; the land continued to be controlled by the Rensselaer family for two-hundred years [2].

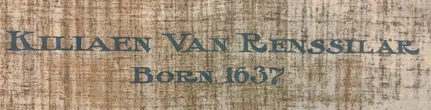

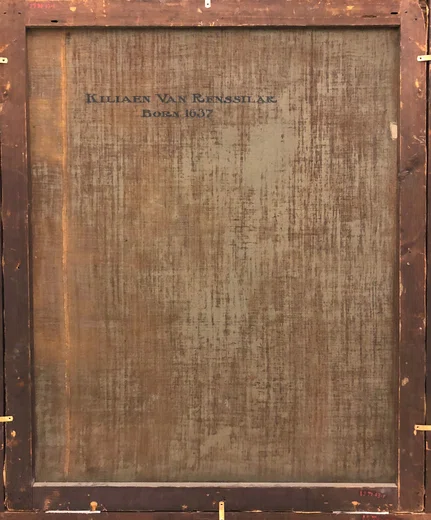

The original patriarch of Rensselaerwyck was Kiliaen van Rensselaer (1586-1643), who made his wealth as a founder of the Dutch West India Company, trading in both diamonds and pearls [3]. There are multiple patriarchs in the family named Kiliaen, so identification may become confusing. The fifth Patroon to control the manor, another Kiliaen van Rensselaer (1687-1719), was the father of both Jacobus and Jan Baptist. Interestingly enough, an inscription on the reverse of the Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer reads: Kiliaen Van Renssilar/ Born 1637 (fig.3). The inscription is wrong, and may relate to the fourth patroon of the manor…Jacobus’ grandfather, who was also named Kiliaen. As the responsibility of the prosperous manor was passed down, their older brother, Jeremias van Rensselaer took over the estate in 1719 around the time that several of the AIHA Dutch patroon portraits were made. With all of that power and accumulated wealth, the Rensselaer family could afford the best materials that were available at the time—canvas, pigments, and skill.

Fragile Canvas Supports | Paintings as Three-dimensional Objects

When paintings are seen as three-dimensional objects and not just flat images, it is easier to understand the problems they develop as they age. Both paintings are executed on linen (est.) canvas. A key thing about canvas is that it cannot be unsupported – it must be kept under tension on an auxiliary support . As a hygroscopic material, canvas on its own can wrinkle, crease, and distort (fig. 4)--- a canvas stretched over a wooden framework (typically, a four membered stretcher or strainer) will stay flat due to the tension provided by the attachment to the framework.

FIGURE 4. An unstretched, linen canvas below the wooden stretcher displays wrinkles, creases, and distortions prior to stretching and adding tension from the stretcher support

The relatively untouched Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer seems to have its original wood auxiliary support (figs. 4-5). A fairly simple four-member wood strainer with half-lap joins and irregular, hand-forged nails. There is no hesitation in referring to the strainer as original because there is no sign on the margins that the canvas was ever secured to another support; additionally, the paint ends exactly at the edge of the strainer, corresponding to its irregularities. It’s rare and rather exciting that a three-hundred-year-old strainer is still attached to the painting!

When a strainer or stretcher begins to fail in its function, they are often replaced. The Jan Baptist strainer was replaced decades ago with a new, stronger stretcher. The Jacobus strainer is aging with weak joins and breaks, highlighting another area of decay that will flag conservation intervention. However, given the importance of preserving original artifacts such as this 18th century strainer, every effort will be made to keep the painting and strainer together as long as possible.

Eighteenth Century Methods of Stretching and Sizing canvas

For both Rensselaer portraits, John Watson used a plain-weave, linen (est.) canvas with similar thread counts of 19" x 18” in the warp and weft directions; the canvases are coarser and have a slightly open weave compared to the fine, tight weave canvases used by Watson’s contemporaries, such as Nehemiah Partridge. The Portrait of Jacobus Rensselaer is unlined and remains surprisingly untouched -remarkable for a painting of its age and size. The original canvas margins are present, although very narrow, and still held under tension. This provides a wealth of information on the artist’s materials and practices: type of canvas support, size of the canvas bolt that the artist purchased to make larger or smaller portraits, and the methods used to prepare and stretch the canvas to its auxiliary support.

There are clues to these aforementioned materials and techniques that take careful observation. For instance, small holes along the very edge of the tacking margins (fig. 6)---between the tacks with thread distortion--- indicate the artist used a rope looming technique common in 17th and 18th Netherlandish preparatory practices for sizing canvas. This is one particular way to stretch a canvas prior to attachment to its wooden support; it was common to both Anglo and Netherlandish artists after the infiltration of emigrant Dutch artists to Great Britain during the 17th century.

FIGURE 6. Detail of the small holes along the very edge of the tacking margins belonging to the Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer

Using the “Dutch method”, canvas is stretched by sewing a rope through the edge of the canvas and looping it over a wood frame (fig. 7). A water-based glue is applied and the canvas tightens as it dries, pulling against the ropes and distorting the weave around the rope holes. This method of preparing the fabric creates a telltale pattern: this distortion is called primary scalloping or cusping and refers to the swoops locked into the canvas. The sizing locks up the weave, making it ready to receive the next layers of paint without bleeding into canvas fibers; it also locks in the distinctive thread distortion.

We can clearly see the artist used the rope-loom technique in preparing the canvas by the regularly spaced holes in the margins (fig. 6) with the distinctive bunching of canvas and scallop pattern in the thread weave (fig. 8). What else does the margin reveal about the preparation of the canvas? The unpainted canvas margins and the paint application that ends at the strainer’s edge tell us the sized canvas was stretched onto this strainer and secured with tacks before the artist began the painting process; this and the single tack history make it clear the painting is on its original wood support.

Seams and Selvedge

There is more information we can gather on fabric supports prepared in early 18th century Albany. The lined Portrait of Jan Baptist van Rensselaer measures 48 1/2" (H) x 39" (W), while the Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer is 36 1/4” (H) x 29 ½” (W); slight differences in size may be attributed to the artist or client’s preference and changes that occurred to the size of Jan Baptist’s portrait due to previous restoration campaigns.

Both portraits have a vertical seam that is visible on the reverse and the front of the paintings --tightly stitched and flat—joining two pieces of canvas to achieve a grander sized final painting (figs. 9-12).

FIGURE 11.

The front of Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer. The vertical seam is located through the curtain on the right side of the composition.

FIGURE 10.

Raking light detail of the vertical seam on the reverse of Portrait of Jacobus van Rensselaer

The size of the canvas roll the artist used determines the size of the painting or the number of seams necessary to create the size desired by the client or the artist. Keep in mind that in the eighteenth century, canvas was not made specifically for artists and they would use what was available to them: canvas produced for other industries like garments, sails for ships, mattress ticking, etc. A few examples of other canvas supports have been used by Watson’s contemporaries in AIHA’s collection: Nehemiah Partridge has used fine, tight weave canvas to create smaller and full-length portraits as well as mattress ticking fabric. As a traditionally trained artist working for the Rensselaer Family, John Watson presumably had better connections and was paid more for his portraits; this may account for the coarse-weave linen used in the portraits of Jan Baptist and Jacobus.

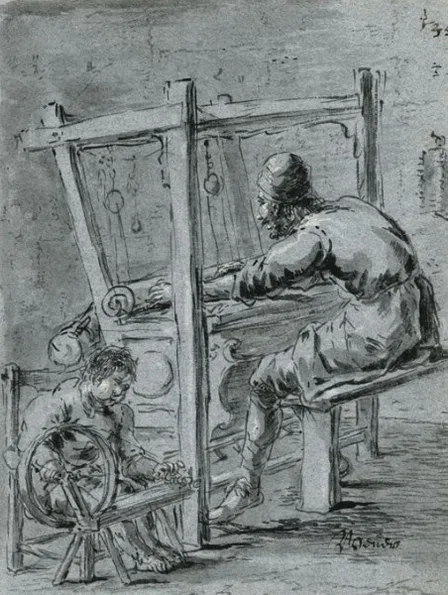

FIGURE 13.

Weavers, Leonaert Bramer, c. 1650–1655, Prentenkabinet der Rijksuniversiteit Leiden, Leiden J. Image accessed at Essential Vermeer [5].

FIGURE 14. Detail of a selvedge edge

FIGURE 15. Detail of a cut edge

When Supports Fails | Past and Present Conservation Interventions

Over time, changes in both the wooden and fabric support due to damage or aging may result in uneven tension, failure or deterioration of the wooden stretcher, and/or tears or lacunae in the canvas. The Portrait of Jan Baptist suffered this common fate sometime in the past 70 years; the painting lacks margins (commonly lost), is currently wax-lined to a secondary canvas, and stretched over a substantial six-membered, wooden stretcher. The 20th century lining is stable and sympathetically applied, unlike other wax-lined paintings in the same collection that required the removal of their wax-resin lining canvases. This auxiliary support (fig. 16) is likely good for another hundred years, and for aforementioned reasons, the Jan Baptist portrait is more stable due to its lining canvas and a sturdier auxiliary support. However, since the auxiliary canvas covers the original canvas, some of the original details and information about the materials and techniques Watson employed for these portraits are either covered or lost.

CONCLUSIONS | NEW INTERVENTIONS

After 300 years, the Jacobus Van Rensselaer canvas and stretching is just barely hanging on –and a conservator needs to consider preservation of original information without neglecting the structural condition; it is a delicate balance between preservation and respecting the historical integrity of what has survived.

In the recent treatment, steps were taken to prolong Jacobus Van Rensselaer‘s un-lined state and preserve its original features, while trying to stay one step ahead of both current & future problems. Treatment was focused on areas identified as prone to failure: the margins and wooden support. Reemay was adhered to the outside of the tacking margins as an reinforcement that provides more support and allows for pulling even tension without disrupting the original canvas edges. The reemay protects the margins from abrasions but also takes some of the stress of holding onto the strainer as it is heated into place with Beva film. While there was a tradeoff in partially covering the margins, it was a decision that slowed margin failure and preserved original materials for another 30-50 years.

The vulnerability of the margins and seams makes it clear why paintings, like the portrait of Jan Baptist, end up being lined to a secondary canvas and why it is so unusual to find an early eighteenth century painting in original condition-- tension, gravity, contact with acidic and corrosive materials, embrittlement with age and handling-- all contribute to margin failure. Even without outside damages --such as tears, punctures, or (horror of horror) water and fire damage –even without disasters a canvas margin has a limited functional lifespan.

Options to preserve and protect original condition center on prevention and begin before the painting ever needs to see an art conservator. Benefits like a secure environment, reasonable climate control, safe storage and display, safe handling, and a bit of luck in avoiding natural disasters --all can play a significant part in allowing a painting to survive intact through hundreds of years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

In March of this year, both Monsterrat Le Mense and Mary Holland lectured on the supports and the nature of their conservation treatment for the Albany Institute of History and Art. See their talk below:

Acknowledgement

We would like to express thanks to the Stockman Family Foundation for their generous support in funding the conservation of the wonderful collection of Dutch Patroon paintings belonging to our consortium member, the Albany Institute of History and Art (AIHA). We'd also like to thank AIHA for their enthusiasm and support during this project.

Photography Credit | Matt Hamilton and Maggie Barkovic

REFERENCES

[1] “John Watson (American Painter ).” Wikipedia, Wikipedia Foundation, 25 April 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Watson_(American_painter)

[2] “Kiliaen van Rensselaer (merchant).” Wikipedia, Wikipedia Foundation, 3 May 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiliaen_van_Rensselaer_(merchant)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Image accessed at http://www.essentialvermeer.com

[5] Image accessed at http://www.essentialvermeer.com