ART CONSERVATOR

DIGITAL

A PUBLICATION OF THE WILLIAMSTOWN + ATLANTA ART CONSERVATION CENTER

VOLUME 15. NO.2 THE

HUDSON

VALLEY

LIMNERS

THE HUDSON VALLEY LIMNERS | PRESERVING THE LEGACY OF DUTCH PATROONS

MAGGIE BARKOVIC | ASSOCIATE PAINTINGS CONSERVATOR

In 2018, the Director of the Williamstown Art Conservation Center and Department Head of Paintings Conservation, Tom Branchick, initiated a survey of the culturally significant collection of early 18th-century limner portraits in the collection held by the Albany Institute of History and Art. The Stockman Family Foundation awarded a generous grant of $238,000, resulting in the conservation of thirty-five portraits.

This survey addressed deterioration and compromised supports for long-term preservation and exhibition at AIHA. Branchick's mission was to see this collection treated during his tenure at the WACC. Five of the paintings are currently on display in the Institute, while the remaining are presently being treated at the WACC. This group of paintings includes a crown jewel of the collection: the first full-length portrait of a woman painted in the United States: Portrait of Ariantje Coeymans by Nehemiah Partridge (c. 1683-1737) (fig.1) [1].

THE DUTCH PATROONS

This collection of Limner or Hudson Valley Patroon paintings were made between 1690-1740 and document the prosperous descendants of Dutch Settlers that cultivated the Hudson Valley before the fall of New Netherlands to the British Empire in 1664. In early 18th century Britain, the production of art was still relegated to the wealthiest members of society until Dutch migrant artists came to England after the economic demise of the Golden Dutch Empire. These Dutch migrant artists reformed the British art market by the mid-18th century by disseminating art commissions amongst the middle class due to being more affordable than British artists [1]. Unlike their British counterparts, the Dutch Golden Age produced an art market accessible to the working classes [2]. It is no surprise then, that this community of Dutch patroons commissioned portraits under the elite rule of the British Crown.

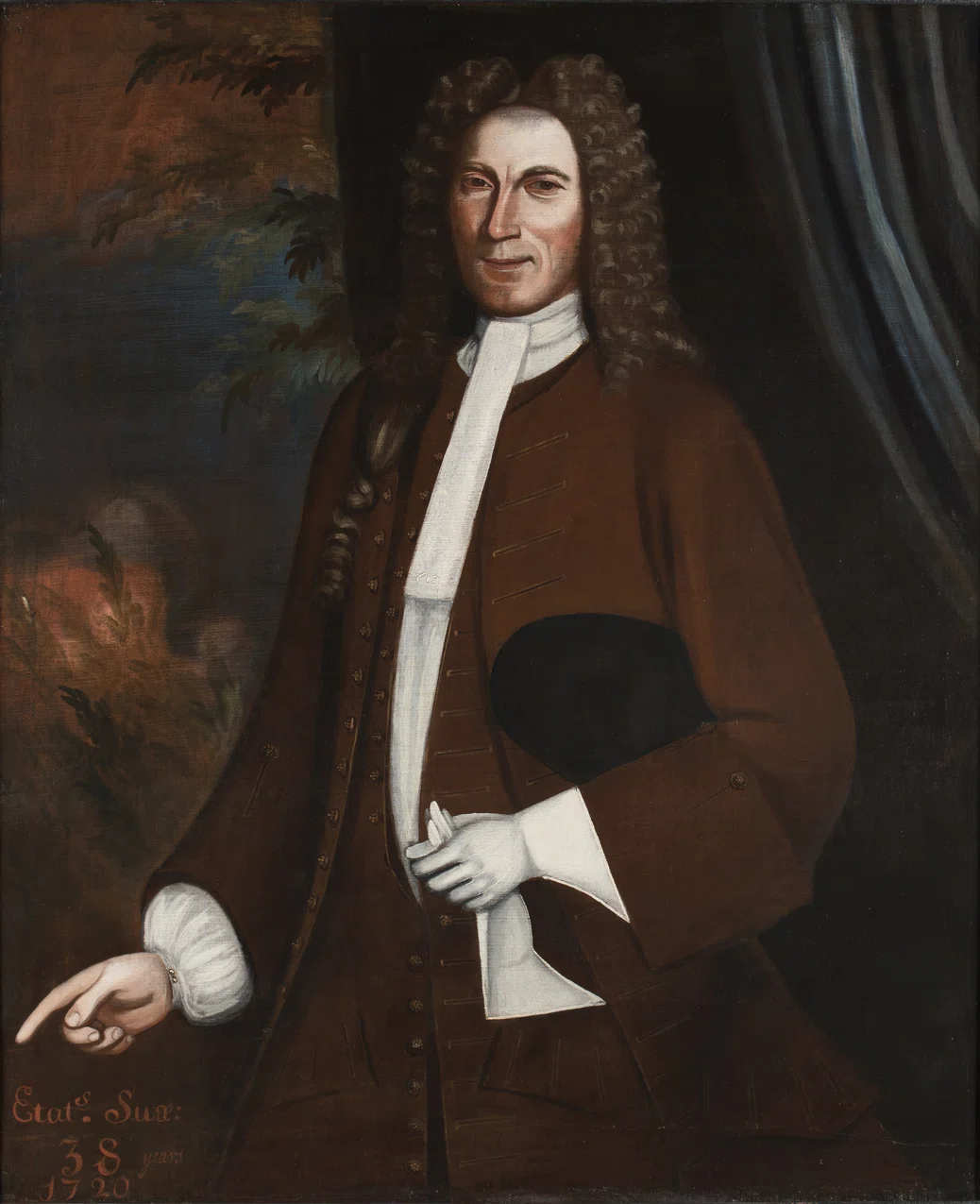

The Dutch Patroons represented in this collection were among the earliest colonists, born on American soil after the fall of New Netherlands to the British in 1664 [3]. The first subjects were prosperous landowners and merchants from New York City, such as the Van Rensselaers, Schuylers (fig.2), Wendells, and Ariantje Coeymans; afterward, less wealthy merchants and farmers followed suit [4]. An early 20th-century art historian, James Flexner, designated these portraits as the first distinctive school of American Art [2]; they are some of the earliest examples of art in America and artifacts representative of the Dutch material culture that survived English rule [5].

THE HUDSON VALLEY LIMNERS | Understudied Pioneers in American Portraiture

Many of the portraits they produced are primitive in style and incorporate motifs adapted from eighteenth-century British material culture [6]. Several emigrant artists are represented from Netherlandish, English, and Scottish heritage: Evert Duyckinck III (c.1677‒1727), Gerardus Duyckinck I (c. 1695‒1746), Nehemiah Partridge (c. 1683-1737), John Watson (c.1685‒1768), Pieter Vanderlyn (c.1687‒1778), the Pierpont Limner (active c.1710‒1716), John Heaton (Heaten) (active c. 1730‒1745), and John Wollaston (active c. 1736‒1775).

This group of craftsmen, described as Limners, painted these portraits with little formal training—however, there is much that is unknown about this group of painters regarding their identification or training [7]. The term, “limning” originally described the production of small watercolors, but developed in the 17th century to include untrained portrait painters [8].

Art Historians Mary Black and Thomas Flexner were pioneers in researching these artists and identifying their hands by grouping the paintings through similar aesthetic qualities [9-10]. Despite Black's prolific work in exploring the identity of various limners and their body of work, few pictures from this genre have firm attributions. Only a few artists have been identified by name, while others simply go by Limner. Considering that the portraits may have been made in a studio by more than one hand, attribution is made all the more difficult. The body of work that the Limners produced is expansive: numerous portraits are owned by several important museums and galleries but remain in storage, away from the public eye, and understudied. It is all the more the reason why the paintings department at the WACC had the privilege to have funding and the joyous opportunity to study and treat such a wide variety from this genre within this impressive collection held by AIHA.

This group of craftsmen, described as Limners, painted these portraits with little formal training—however, there is much that is unknown about this group of painters regarding their identification or training [7]. The term, “limning” originally described the production of small watercolors, but developed in the 17th century to include untrained portrait painters [8].

Art Historians Mary Black and Thomas Flexner were pioneers in researching these artists and identifying their hands by grouping the paintings through similar aesthetic qualities [9-10]. Despite Black's prolific work in exploring the identity of various limners and their body of work, few pictures from this genre have firm attributions. Only a few artists have been identified by name, while others simply go by Limner. Considering that the portraits may have been made in a studio by more than one hand, attribution is made all the more difficult. The body of work that the Limners produced is expansive: numerous portraits are owned by several important museums and galleries but remain in storage, away from the public eye, and understudied. It is all the more the reason why the paintings department at the WACC had the privilege to have funding and the joyous opportunity to study and treat such a wide variety from this genre within this impressive collection held by AIHA.

CLICK THE ARROWS TO SEE A RANGE OF PORTRAITS IN THIS COLLECTION THAT HAVE BEEN TREATED AT WACC. THE IMAGES ARE SOURCED FROM AFTER TREATMENT.

The Project | Preserving the Earliest Portrait Paintings in America

The first survey of the Dutch Patroon paintings by the WACC was initiated in the early 1990s; both myself and Mary Holland completed the survey in the fall of 2018. Both past treatments and age-related deterioration resulted in structural instability and aesthetic problems rendering the paintings either unstable or unexhibitable.

The collection represented in this survey are all on canvas supports, except for two on wooden panels. Twenty-six of the paintings on canvas were structurally compromised by failed wax-resin linings, resulting in cupped paint, cleavage, and paint loss. Fifteen of the paintings had raised paint and flake losses; these were exceptionally vulnerable and required over-all consolidation to prevent further loss. Both panels exhibited splits and were structurally unstable. Some previous retouching and fills had not aged sympathetically. In addition, twenty-seven of the paintings had deteriorated layers of varnish, which exhibited yellowing, uneven saturation, and in some cases, delamination. These issues would have exacerbated over time, risking further damage the longer treatment is delayed— the funding. Intervention was necessary for their long-term stability and was costly, prompting the essential need for grant funding and support by the Stockman Family Foundation.

Several of the frames within this collection are impressive, including one seventeenth-century Dutch frame that appears to have been imported from the Netherlands. Many of them exhibited flake losses of gilding and gesso or did not completely house the paintings. The conservation of the frames was included in the grant. While the treatment of the frames is not covered in this issue, it was an integral part of this project; Christine Puza, Department Head of Furniture and Frames Conservation, collaborated with the Department of Paintings Conservation to treat this collection.

The Crown Jewel | The Portrait of Ariantje Coeymans by Nehemiah Partridge

The Portrait of Ariantje Coeymans (fig. 3) is one of two known to be made by Nehemiah Partridge, also known as the Aetatis Suae Limner. The rare, full-length portrait features Neo-classical architecture against an apocalyptical sky with reds, pinks, and oranges. Partridge often borrowed his compositions directly from British Mezzotints depicting British Aristocracy [11]; the portrait of Ariantje has been borrowed from a mezzotint by G. Beckett after Geoffrey Kneller’s Portrait of Lady Bucknell [12].

This painting is significant in many ways, like the woman Ariantje herself. It is the first full-length portrait of a woman in America. By 51, she was a powerful landowner, having built one of the largest Dutch-style houses in the Upper Hudson Valley (fig.4). It is fitting that Ariantje Coeymans was a woman before her time: she commissioned this portrait at the age of 51 when she married for the first time to a man twenty-three years younger [13]. The house is still standing and has been beautifully renovated in the early 21st century (fig.5). The commanding portrait is a tribute to her legacy as a prosperous female landowner when that was almost improbable—at least, by British standards. She is still a force within the house as the owners have enthusiastically displayed a replica of Ariantje’s portrait in a prominent place so that she may still look upon her estate with pride [14].

FIGURE 3.

Partridge, Nehemiah, Portrait of Ariaantje Coeyman, c.1718

oil on canvas, 80 1/2” x 50 1/2”. Before Treatment.

A Glimpse into Nehemiah Partridge

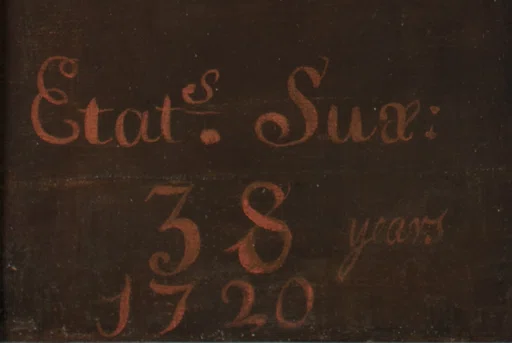

Over fifteen of the Dutch Patroon portraits conserved by the WACC have been painted by Nehemiah Partridge. Nehemiah Partridge, was born in 1683 in Portsmouth, NH. His father was a wealthy merchant who became Lt. Gov of New Hampshire [15]. Nearly all of his paintings have the phrase “Aetatis Suae” inscribed, followed by the sitter’s age and date of the picture; this attribute had led to several of his paintings being attributed to the anonymous “Aetatis Suae” Limner [16]. He started in the Boston area as a japanner, the European imitation of Asian lacquerwork for decorative objects and furniture; he also sold paints [17]. Most Limner’s were “jack-of-all-trades”, advertising various decorative art skills. It is uncertain how his experience as a decorative painter influenced his materials and techniques as a portrait painter; however, in many of his portraits, there are small jewel-like details such as jewelry or buttons have been done with more confidence and care than other parts of the composition such as drapery. By 1717, he was living in New York, and his profession was recorded as Limner in 1718 when he completed the full-length portrait of Ariantje Coeymans.

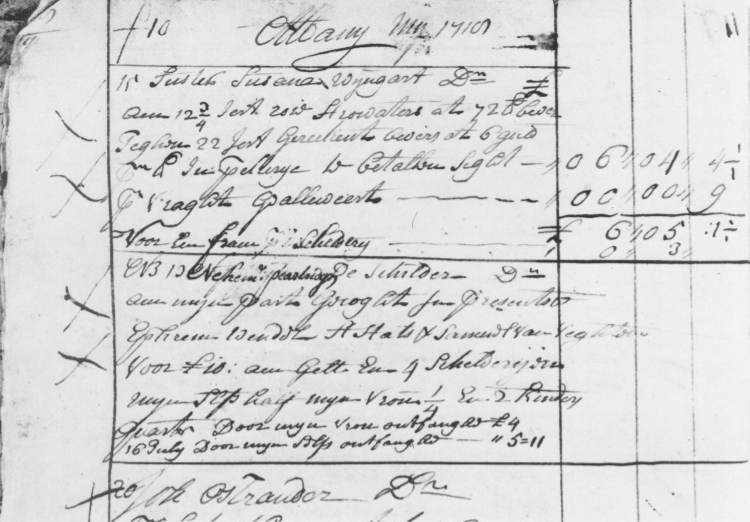

How did a limner like Partridge gain the commission of a patron like Ariantje when other prosperous Dutch limners like Gerardus and Evert Duyckinck were available? He may have captured this plethora of commissions through Everett Wendell, whose relative was a Boston merchant. Art Historian, Mary Black, whose research has been consequential for the study of these painters, identified an agreement between Everett Wendell and Partridge to trade a horse for ten pounds and four portraits (1718) attributed to the Aetatis Suae Limner [18].

FIGURE 6.

Detail of an inscription from a portrait by Nehemiah Partridge. Prior to attribution by Black, he was named as the "Aetatis Suae Limner".

FIGURE 7 .

A copy of the agreement that Mary Black found at the New York Historical Society and used to identify the hand of Nehemiah Partridge. He is listed here as "Nehemiah Peartridge De Schilder" [18]. Schilder means artist in Dutch.

Reversing Treatments of the Past

The portrait of Ariantje, like many others in the collection, had condition issues that required conservation treatment for its long-term preservation. These issues include: deteriorated synthetic and natural resin varnish surface coatings, a structurally compromised support due to a failed wax-resin lining, cupped paint, paint loss. Abrasion to the paint film is present and appears as paint loss, revealing the red ground layer present in several of Partridge’s paintings. Due to the failure of the wax-resin to consolidate adhesion between ground and paint layers, there was localized raised paint and loss that was visually disruptive.

Unfortunately, previous interventions don’t always age sympathetically. Aesthetic issues include mismatched or discolored retouching, fills that cover original paint, and were texturally distracting.

After the painting was cleaned, relined, and stretched, it was ready to be filled and retouched. In some cases where lacunae in the canvases were large, small inserts of linen fabric were cut to the size of the hole and attached to the surrounding canvas fibers to provide support for the fill and canvas weave texture to mimic the thinly painted surface. An isolating layer of a reversible synthetic varnish was applied prior to filling and retouching. Filling and retouching were used to reintegrate damage and abrasion (figs. 8-9).

An Initial Step Towards Further Research

Outside of academic institutions, it can be difficult for conservators to have the time or the resources to research the materials and techniques present in the paintings they treat. It was essential to understand localized discoloration, fading, and changes in the paint film to inform our approach to treatment. For instance— some areas contain delicate glazes made with Red Lake that have faded or copper-containing glazes that have turned brown. These changes are inherent to how these pigments age and may occur due to an array of reasons such as artist preparation, oxidation, and light-induced fading.

As a self-proclaimed Dutchophile that had the privilege of living and studying art conservation in Holland, I wanted to know more about what materials these artists used and how they prepared their paintings. Prior to British rule, there was a rich trading market in New Netherlands regulated by the Dutch West India Company; permanent posts were established in Beverwyck (present-day Albany) and New Amsterdam (present-day New York City) in 1625. Trade depended on Dutch ships from Amsterdam and local Native American tribes [19]. After the fall of New Netherlands to the Great British Empire in 1664, the British government forbade trade with the Netherlands, but many colonists and Native Americans preferred Dutch-manufactured goods. This resulted in a smuggling trade and prompted many Dutch-American settlers to train as craftsmen; the smuggling network was particularly existent in the upper Hudson River Valley, where the power of the Rensselaerwijk Patroonship remained strong [20]. This undocumented trade network raises specific questions about the genesis of their materials and techniques and how it may relate to either their Dutch or British heritage.

In art conservation scholarship (and art history, which commonly does not study the physical materiality present in artworks), the materials and techniques used by the Hudson Valley Limners have not been studied. Scholarship in these areas could provide an important understanding about trade in early Colonial America; pigments could be imported, traded between Native Americans and colonists, or made from indigenous species. Considering the number of questions that still have yet to be answered, it will take years and multiple scholars from various disciplines to study the materials and techniques of these influential artists.

While working on portraits by Nehemiah Partridge and Evert Duyckinck, I saw what looked like the delicate and rich glazes of red lake that I loved learning about during a red lake workshop carried out at the Courtauld Institute of Art. It is an organic dye, typically ground in oil or resin, that is often applied on top of bright red vermillion for the details of rosebud lips and petals— and in the case of Partridge, mixed with other pigments to create an almost fluorescent and apocalyptical sky in the background of his sitters (figs. 10-11). During the 18th century, red lake could be made from various sources spanning several continents [21]— each type and their subsequent preparation impacts the color, richness, and stability of the glaze— and, therefore, its value. Prior to British rule, detailed council notes of trade in New Netherlands list importing cochineal (from silk) and various dyewoods from their colonies in the Caribbean [22]. It is uncertain if various forms of red lake continued to be imported by the Dutch settlers or if this changed when the British took over the colonies. Furthermore, it is of interest how these types of pigments were prepared and used by the untrained Hudson Valley Limners.

I asked Rachel Childers, our Postgraduate Fellow, if she would pursue the study of red lakes in the collection of Dutch Patroon works treated at the WACC as a first step towards understanding more about the types of materials present in the collection. Rachel is currently researching the types and occurrences of red lake in the collection at AIHA and led a red lake-making workshop for our pre-program interns. Rachel's analysis of red lakes in the AIHA Dutch Patroon portraits is a collaborative project between the WACC and Williams College Chemistry Department.

FIGURE 10.

There is red lake that has faded in the whitish rose petals in a portrait painted by Nehemiah Partridge

FIGURE 11 .

Partridge used red lake as a glaze and in mixtures to produce rosy and often apocalyptical looking clouds.

BACK ON DISPLAY

A future exhibition at the Albany Institute of History and Art will display the fruits of WACC and AIHA’s labor in preserving this important collection of early American Portraiture. We hope that you enjoy studying the brush strokes of Hudson Valley Limners and viewing the faces of the Dutch patroons that helped shape the colony of New York —they cultivated and established much of the landscape between Albany and New York City.

REFERENCES

[1] “Ariantje Coeymans Verplanck”. https://www.albanyinstitute.org/details/items/ariantje-coeymans-verplanck-1672-1743.html. Accessed March 03, 2020.

[2] Karst, S. (2013). Off to a new Cockaigne: Dutch migrant artists in London, 1660–1715. Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 37(1), 25-60. Retrieved Feb 18, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24365145. pp. 1-2.

[3] Kenney, Alice P. "Neglected Heritage: Hudson River Valley Dutch Material Culture." Winterthur Portfolio 20, no. 1 (1985): 49-70. Accessed Feb 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181000.p. 64

[4] Flexner, James. First Flowers of our Wilderness (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1947), 69.

[5] Ruby, Louisa Wood. " Chapter One. Dutch Art And The Hudson Valley Patroon Painters". In Going Dutch: The Dutch Presence in America 1609-2009, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2008) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163683.i-367.10 p. 2.

[6] Belknap, Waldron Phoenix, and Charles Coleman Seller. American colonial painting: Materials for a history. (Prepared for publication by Charles Coleman Sellers.). 1959. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

[7] Black, Mary. "Contributions toward a History of Early Eighteenth-Century New York Portraiture: Identification of the Aetatis Suae and Wendell Limners." American Art Journal 12, no. 4 (1980): 5-31. Accessed December 1, 2018. doi:10.2307/1594219.

[8] Gitlitz, Michael. 1997. From limner to aesthete: two hundred years of portrait and figure painting in America. New York, N.Y.: Hirschl & Adler.

[9] Black, Mary. "Contributions toward a History of Early Eighteenth-Century New York Portraiture: Identification of the Aetatis Suae and Wendell Limners.”

[10] Flexner, James. First Flowers of our Wilderness.

[11] Belknap, Waldron Phoenix, and Charles Coleman Seller. American colonial painting: Materials for a history. pp. 271-329

[12] Belknap connects the portrait’s composition to G. Beckett after Sir Godfrey Kneller, The Lady Bucknell, mezzotint. Illus. in Remembrance of Patria, p. 249.

[13] “Ariantje Coeymans Verplanck”. https://www.albanyinstitute.org/details/items/ariantje-coeymans-verplanck-1672-1743.html. Accessed March 03, 2020.

[14] From conversation with Douglas McCombs, Chief Curator at the Albany Institute of History and Art, March 16th, 2021.

[15] Black, Mary. "Contributions toward a History of Early Eighteenth-Century New York Portraiture: Identification of the Aetatis Suae and Wendell Limners.” p. 16.

[16] Ibid., p. 9.

[17] Ibid., pp. 15-16

[18] Ibid.

[19] Jacobs, Jaap. 2009. The colony of New Netherland: a Dutch settlement in seventeenth-century America. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

[20] Kenney, Alice P. "Neglected Heritage: Hudson River Valley Dutch Material Culture." Winterthur Portfolio 20, no. 1 (1985): 49-70. Accessed Feb 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181000. p. 51

[21] Kirby, Jo. 2014. Natural colorants for dyeing and lake pigments: practical recipes and their historical sources. London: Archetype Publ.

[22] Van Laer, Arnold J. F., Kenneth Scott, Kenn Stryker-Rodda, and Charles T. Gehring. 1983. New York historical manuscripts, Dutch. Council minutes, 1652-1654 5 5. p. 162