ART CONSERVATOR

DIGITAL

A PUBLICATION OF THE WILLIAMSTOWN + ATLANTA ART CONSERVATION CENTER

VOLUME 17 NO.1 Appendix | Folio Placement, Transcriptions, and Translations

BROOK PRESTOWITZ | ASSOCIATE CONSERVATOR OF PAPER

Dr. Joel Pattison | Williams College Assistant Professor of History

Despite the personalization of a book of hours, the content would follow a general organization that shared this type of manuscript. Chart 1 offers an estimation of where the treated folios are located within the book of hours. The illuminated side of each of the folios has been referred to as the recto throughout this essay. However, the actual rectos and versos of each folio as they would have been found in the bound manuscript is indicated in chart 2.

CHART 1.

An estimation of where the folios are located within the book of hours

CHART 2.

An estimation of the order of the folios as they would have been bound in a book of hours

In the fifteenth century, religious texts were written in Latin, which was considered by some to be the sacred language. Others saw the use of Latin as a way of using a universal language to unify the Church in the west. The Latin of Christianity adapted elements from Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek and is therefore not comparable to Latin used in ancient Rome [1]. While Latin remained the official language of the church, it was not uncommon for the vernacular to be used intermittently in ceremonies or interchangeably with Latin in a book of hours [2]. This is true for the folios in this case study. The first line introducing the saints in each folio, which is part of the rubric written in red ink, is in French.

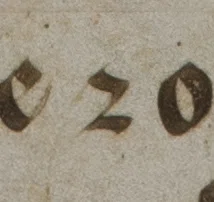

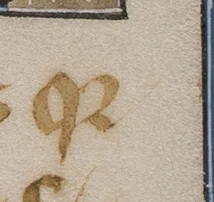

The scribes used littera textualis, which is a type of blackletter or gothic script, to write the text in the folios. Littera textualis could be written in two formats: document form, used when writing documents, and bookhand form, used when writing a manuscript like this book of hours [3]. A sort of shorthand method of combining letters or using a single letter to stand for certain words is characteristic of this font. For example, the Latin word et (and) is represented by the letter ‘r’ (fig 1); the strand of letters pro is represented with the letter ‘p’ with a fancy tail (fig 2) [4]. Certain letters would be combined such as the letters ‘c’ and ‘I’ or the letters ‘m’, ‘n’, ‘i’ and ‘u’ in a practice referred to as biting [5]. Other characters were written in the space above a line of text (fig. 3, fig. 4)

The scribes used littera textualis, which is a type of blackletter or gothic script, to write the text in the folios. Littera textualis could be written in two formats: document form, used when writing documents, and bookhand form, used when writing a manuscript like this book of hours [3]. A sort of shorthand method of combining letters or using a single letter to stand for certain words is characteristic of this font. For example, the Latin word et (and) is represented by the letter ‘r’ (fig 1); the strand of letters pro is represented with the letter ‘p’ with a fancy tail (fig 2) [4]. Certain letters would be combined such as the letters ‘c’ and ‘I’ or the letters ‘m’, ‘n’, ‘i’ and ‘u’ in a practice referred to as biting [5]. Other characters were written in the space above a line of text (fig. 3, fig. 4)

FIGURE 1.

The letter ‘r’ used as a shorthand for ‘et’ the Latin for ‘and’. This example is taken from the text on the verso of the Pentecost folio.

FIGURE 2.

An example of the ‘cp’ shorthand character for ‘pro’ found in the text on the recto of St. Pope Urban.

FIGURE 3. Strange character that looks like the number ‘9’ used as shorthand for the letters ‘us’ meant to be at the end of the word ‘orem’ to complete the word ‘oremus’ found in the top right corner of the text on the verso of St. Ives.

FIGURE 4.

Strange character that looks like an apostrophe used to add the letter ‘s’ to complete ‘deu’ to realize the word ‘deus’, found in the text on the verso of St. Ives.

TRANSLATING THE INSCRIPTIONS ON THE FOLIOS

**Translation of this folio has indicated that the initial identification of this scene as the Pentecost may be incorrect. All Saints Day is celebrated the Sunday after the Pentecost Sunday. However, the text in this folio shares more similarities with the other suffrages to the saints than the texts that might be associated with the Hours of the Holy Spirit. For the sake of consistency, the folio will continue to be referred to as Pentecost.

REFERENCES

[1] Virginia Reinburg, French Book of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1400-1600, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 92-93.

[2] Ibid, 96.

[3] “2.5 The gothic Scripts-Textualis” School of Advanced Study University of London. https://port.sas.ac.uk/mod/book/view.php?id=891&chapterid=506 (accessed September 8, 2022).

[4] Personal correspondence with Dr. Joel Pattison, Williams College Assistant Professor of History.

[5] Virginia Reinburg, French Book of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1400-1600, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 94.