A WILD AND FANTASTICAL WORLD

With his lush florid style and signature combination of gilding, glazes, and surface texture, the decorative objects and interiors created by Robert Winthrop Chanler are unmistakable.

His working life spanned the end of the nineteenth century until his early death in 1930, melding fin de siecle decadence with the beginnings of a clear Modern style. Born in 1872 as one of ten children in the wealthy Astor family, Robert Chanler was orphaned at the age of five. Supported by a large inheritance, Chanler and his siblings were raised by a series of trustees at their parents’ estate in Rokeby, New York. His ungovernable and eccentric personality showed itself early: in 1889, at the age of seventeen he was sent to Europe by his guardians. By 1893 he had decided to become an artist and settled in Paris to take classes with several academic artists. He soon found himself stifled by the rigor and “disgusted with the sterile instruction of atelier and academy” [1], and moved to Italy.

Throughout the 1890’s he set upon an intense period of self-directed study, travelling throughout Europe and absorbing visual influences from such diverse sources as Italian Renaissance art, French Gothic cathedrals, the collection of decorative art objects from the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the luxurious excesses of Bavarian rococo. But, it was his serendipitous discovery of a lacquered Asian screen in a Parisian antique shop that planted the seed for what would become a significant part of his artistic repertoire for the greater part of his working life. Declaring the screen “wonderous”, he was at once captivated by its imposing scale and dramatic scheme of gold against a lustrous red and black surface. This awakened “countless aesthetic atavisms, suggesting fascinating possibilities for future development” [2].

The Formation of a Fantastical Artist

Some of his earliest known works are screens and murals that were created exclusively for private residences. The red and gold so-called “Peacock panels”, executed in 1900, were his first significant series. This early work draws from Chinoiserie influences and is suggestive of the Whistler Peacock Rooms, of which Chanler was likely familiar. They were shown in his first solo show held at the Georges A. Glaenzer and Company galleries in March of 1903. Response to the arresting vermillion background and modern stylized designs of the screens were mixed. Of the show the New York Times noted: “The prototype in Mr. Chanlers panels may have been the gorgeous silk hangings from China which are so decoratively insistent that they take the stage themselves and leave no room for other things. Whether in this he has struck a new note is the question” [3]. Despite this, Chanler had no shortage of patrons seeking his services.

Flush with work, Chanler set up his personal residence and studio at 147-149 East 19th street, christening it “The House of Fantasy.” Although only fragments of the heavily decorated interior survive to this day, by all accounts The House of Fantasy was as wild and fantastical as its owner. Extensively decorated with animal imagery in both mural and relief plasterwork, the rooms were living portfolios of his style, which he continually reworked. Chanler was a voracious reader on a wide variety of subjects; his extensive personal library overflowed into the rooms, which were crammed to the ceiling with objects and plants. Not one to simply be content with books about the natural world, however, The House of Fantasy also included a conservatory that held a menagerie of live animals that he used as direct references for his sculptures. His conservatory included tanks full of tropical fish and reptiles, and aviaries of exotic birds. His aviary included flamingos, storks, English ravens, buzzards, and toucans, while his zoological collection burgeoned with animals such as monkeys, sloths, and ringtail lemurs [4]. He continually added to their number by collecting new flora and fauna from his excursions to the tropics and the American Southwest. Chanler entertained often in this raucous space, hosting cocktail parties that would often last for weeks. His contemporary, the writer Henry Tyrell explained:

“only such a place such as this- bachelor living apartments, atelier and

[5]

Despite his outrageously profligate lifestyle, Chanler’s output was prodigious, designing painted and plasterwork room interiors, panels, and screens for a rapidly expanding wealthy clientele. During a period of twenty years, up until the mid-1920’s Chanler primarily produced folding and single-panelled screens; these quickly became a status symbol among the moneyed elite. He was assisted by a stable of skilled artisans that carried out the technical aspects of preparing panels and constructing the bodies of the screens. Each screen required a lengthy and arduous process to execute, even before decoration could be applied.

Chanler enjoyed regular commissions, however, it was The Armory Show of 1913 that propelled his work to its greatest heights. The show first opened in New York and was in many ways a historic event, as it was the first large-scale exhibition of European and American Modern art in the United States. This prominent exhibition was started by a small group of American artists that were known as the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS). It was funded primarily by individuals, many of them the matriarchs of some of the most powerful families in America that were well known by Chanler. The AAPS sought to create an annual exhibition that allowed the inclusion of any media, style, or subject matter, and did not discriminate between the decorative or fine arts. The focus was the observer’s pleasure, by which means any form of expression and medium was included. In addition to Chanler’s screens, the show included an unprecedented wide variety of media and works by American female artists. Although a few of his works had been shown in smaller numbers before, most thus far had been kept in private collections. This event represented the first time that the public would be able to meaningfully experience the work of this artist. The New York venue of the Armory show held at least thirteen works by Chanler, only surpassed in number by the French painter Odilon Redon (70); Odilon was an artist close in kin with Chandler’s aesthetic sensibilities. When the exhibition travelled to Chicago, the catalog listed nine screens with a later addition being “The Orange Birds of Paradise” [6], At both venues, Chanler’s work was given a place of pride, with his largest screen greeting visitors at the entrance to the exhibitions. The show was an immediate success and his work soon garnered a new fevered level of attention and discussion. Newspapers showered the artist with praise, with one declaring him “an original and remarkable man” [7]. His place in the art world was now officially established. The stage was set for the next phase of his career: a designer of decorative interiors, grottos, and murals in Gilded Age estates, which continued until his untimely death at the age of fifty-nine in 1930.

Materials + Technique

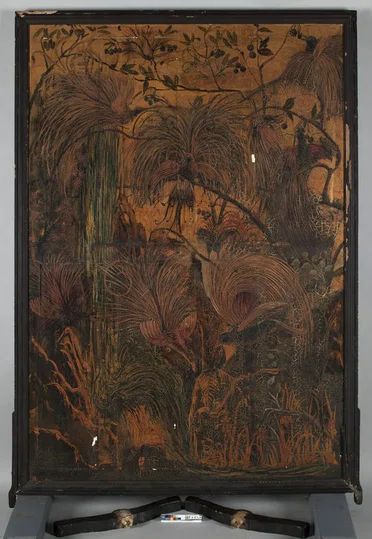

The magnificent Birds of Paradise screen (figs. 1-2), now owned by Tracie Rozhon of Albany, NY, exemplifies the eclectic mix of influences that characterizes Chanler’s work. The luminous gilded surface of the Bird of Paradise side simultaneously brings to mind an Italian icon, Japanese lacquer, cloisonne enamel, and embossed Spanish leather. The reverse of the screen is strikingly solemn, with a depiction of Ravens in a muted green and brown landscape (fig.2). Many of his other single panel screens seem to also share this duality of ornament, with one side a more obvious “front” with bright colors and bolder imagery, and a more subdued reverse. The Birds of Paradise side appears to be a textbook example of Chanler’s working method, with multiple layers of gilding covered by transparent and translucent glazes, not dissimilar to those used in the production of Asian lacquer goods:

Christine Puza | Dept. Head of Furntiure & Frames + Analytical Services

The Treatment of the Robert Chanler Birds of Paradise Screen

ART CONSERVATOR

DIGITAL

“The screens are first made of white satinwood, exquisitely fine, to which is applied a certain kind of fine muslin. Then the process of painting the wood over the muslin for a background upon which to paint is begun. The foundation paint is put on and then rubbed in with skill. Many coats of paint must be applied to obtain the proper finish, which looks like enamel, before the real work of applying the design is begun. Two months are necessary for the first preparation to be made complete, for several coats of paint repeated at intervals must needs take long in drying. Then, when the artist begins his design, the time speeds on into months, even two years or more in some cases, before the eagerly sought-for quality is obtained.

Fig. 3 Across-section from the frame shows seven different layers and reveals the original gilt and bright green paint used for the frame.

1-2) The white and sem-translucent ground , 3) the original paint: bright green and gold, 4) a transparent surface coating 5) umber paint applied by Chanler 6) transparent surface coating 7) present umber paint

The structure of this single panelled screen is similar to several other examples of Chanler’s work, and may have been executed by the same artisan. The style of the feet and framing are identical to his 1912 Leopard and Deer (Death of the White Hart). The central panel of the screen appears to have been constructed in eight sections, four above and four below, separated by a horizontal batten. The decorative panel stands upon bracket feet that were originally joined to the bottom mitre of the frame with a trio of ⅜” oak dowels. These dowels were only 1 inch long, which is a surprising choice given the great weight they are required to support. A decorative molding applied to the sides of the frame provides some support to the feet, but was not originally attached. The frame, made of white oak, is comprised of a simple ogee molding, with doweled and mitred corners.

Hit the arrows to see different details of the techniques used on the front and reverse of Chanler's Birds of Paradise Screen.

These details are sourced from after treatment images.

The wood panels that comprise the central decorative panel have been prepared with a gessoed textile, which was visible through areas of damage and loss. The textile provides a rough surface to apply the gesso preparatory layer; this method is described in sources documenting his working process[1]. The textile had been covered in at least one, and perhaps more than one layer of gesso before having been gilded or painted.

This surface has also been coated with a 'cracking varnish' to produce a bold craquelure pattern overall, some of which has been accented with the addition of gold paint.

There is evidence of a significant change to the composition at the upper right corner on the Birds of Paradise side. This is true to reports that Chanler often worked and reworked his designs. Visible in raking light, slightly raised against the background, is an arcing branch laden with round fruits and a bird. The color of the frame itself has also undergone a significant change. Beneath the flat, umber colored paint is a gilded surface, mottled with brilliant shades of green; visible evidence was supported through the analysis of a cross-section with optical microscopy (fig.3). What drove the decision to cover over this highly decorative surface is unknown; it may have been done to harmonize with the frames of his other works when placed on exhibition.

A Complex Condition

The screen came to the lab for the treatment of physical impact damage sustained during the course of an explosion. During the night of February 1, 2019, sewer gases were ignited by an underground transformer near the owner’s residence, which blew out the windows on the ground floor. No one was hurt, but the screen was thrown up against an interior wall and showered with broken plate glass. The sudden concussive force further damaged an already inherently brittle gessoed surface, resulting in large areas of cracking, lifting and loss, particularly those adjacent or associated with areas that have been previously treated. The sudden temperature and humidity fluctuation when the windows were broken and the interior of the house was flooded with cold exterior air, is also likely responsible for some of the observed damage. Deposition of residue from the products of combustion and other exterior particulate was also a concern. Soot and associated residues can be highly acidic and damaging to painted surfaces.

The bottom ten inches of molding on the lower right corner was cracked completely through; the foot beneath it was broken off where the screws had attached it to the rest of the frame. The wood was very torn and broken in this area, which appeared to have been repaired, drilled, and screwed together multiple times. The other foot was also affected, although not to as great a degree. The rails of the frame had detached from the panels and were freely movable. Overall the screen was dangerously unstable, difficult to handle, and could not stand safely upon its feet.

The gesso layer between the panel and the textile is the site of interlayer cleavage where the surface is beginning to detach from the deeper substrate. There were numerous areas of lifting and bubbled paint that had not yet detached, as well as areas where the bubbled paint has broken open and was peeling back from the gessoed textile underlayer. Observations from images and auction records of other Chanler works suggest that the interface between the gesso layers and the textile, or the textile and substrate, has become unstable over time, with many of his work exhibiting similar condition issues of bubbling and lifting.

Hit the arrows to see different details of the condition issues on the front and reverse of Chanler's Birds of Paradise Screen.

These details are sourced from before treatment images and include details of mismatched over paint, crude fills, flaking, and splits discussed in the article.

The many lifting and bubbling areas on both sides of the screen were consolidated with injections or an application of a mixture of Lascaux® Medium for Consolidation and Lascaux® 498. Heat was applied with a Willard spatula to flatten and set down bubbled and distorted areas as much as possible. Some regions were not able to be completely flattened due to stepping of the painted surface, caused by the shrinkage of the substrate. In cases where the distortion was not able to be remediated, the distortion was supported in place.

A gummed paper label, listing a surprising price of “$100” written in pencil, was removed from the Raven side of the screen by humidifying it with a dampened cotton blotter and lifting it from the surface with a piece of silicone release Mylar. It was placed in a Mylar sleeve and returned to the client.

Deep cracks in the decorative panels were filled with a proprietary wood filler, followed by Flϋgger® when needed to match the impasto texture. The stabilized panels were given a coating of 10% (w/v) Paraloid™ B-72 resin in Xylenes as an isolating varnish. QoR® watercolors and Aquazol® mixed with mica pigments was used for inpainting, followed by further application of B-72 to adjust the gloss. The final result is not imperceptible, particularly where flattening of the surface was not possible; however, this round of inpainting minimizes the appearance of damage and better integrates the reworked areas with the original design.

Losses to the painted surface of the frame were consolidated with Lascaux® Medium for Consolidation and then inpainted with Golden® MSA colors (fig. 4). As there is a gilded and painted surface beneath the brown paint of the frame, it remains easily chipped.

The structural repairs to the frame were extensive. The size of the feet and the construction of the frame were relatively underbuilt to support the weight and size of the screen, and there was evidence of at least two previous courses of repairs where the attachment of the feet to the frame had failed. All remnants of old glue were removed by poulticing with Laponite® synthetic clay and removed mechanically. Broken pieces of the frame were adhered with high tack fish glue. The original trio of 1" dowels that held the feet to the frame were cut flush with the feet. These were returned to the cavity of the frame and adhered in place along with the broken off piece of oak that belonged to the upright rails. A hole was drilled through each foot to accept a 10" lag screw that was used to affix the foot to the frame, and proceed as far up into the rails of the frame as possible. To provide further reinforcement, a heavy steel angle bracket that proceeds across the entire width of the side of the feet and the bottom of the frame was applied.

The work of Robert Chanler remains singular in the world of American Art, an amalgam of decorative styles blending Art Nouveau and the Symbolists with bold Modernistic style in the larger than life way only he could. A new exhibition of Chanler’s work, including this magnificent Bird of Paradise screen, will be on display at the

Planting Fields Museum

in Oyster Bay, Long Island NY.

FIGURE 4. Christine retouches loss on the front of the panel

FIGURE 5. Christine repairs the feet of the frame

FIGURE 6.

After Treatment,

Click to view a larger imageFIGURE 7 .

After Treatment, Click to view a larger image

REFERENCES

[1]

Christian Brinton, The Robert Winthrop Chanler Exhibition (New York : Kinggore Gallery), 1922.

[2]

Brinton, 1922.

[3]

“Color schemes for walls”, New York Times, March 15, 1903.

[4]

“Studying angelfish for the purposes of Art” Washington Post, March 16, 1911.

[5]

Henry Tyrell, “Bob Chanlers Creepy Art,” San Francisco Sunday Call, March 9, 1913

[6]

Harriet Monroe, “Art Exhibition Opens in Chicago” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 25, 1913

[7]

Harriet Monroe, “New York has at last achieved a cosmopolitan modern exhibit”. The Chicago Sunday Tribune, February 23,1912, B6

[8]

Ada Rainey, “The decorative screens and mural paintings of Robert Winthrop Chanler”, House Beautiful (March 1918): 108